The Crucial Difference Between Horseshit and Bullshit

I love the words of baseball. These words were new to me when I started covering the sport for the San Francisco Chronicle in 1979, me a thirty-four-year-old Jewish guy from Brooklyn who’d never heard real live Baseball Talk. A fastball is heat, cheese, gas. A batter looking exclusively for a fastball is looking dead red. A curveball is the hook or Uncle Charlie. Other words for pitches – spitter, splitter, sinker, screwball, knuckler, beanball. A strikeout is a punchout. A base hit is a knock. Baseball players use all these words, and they are more colorful than words I studied for the SAT like audacious – my mother bought me a book of SAT words.

But one word more than any expresses the culture of baseball. Excuse me for writing this and if you are sensitive, please stop right here, but the most important, most fundamental, most descriptive word in baseball is horseshit. I learned this to my astonishment when I was a rookie sports writer. Every major league player you remember or who currently plays understands the nuances of the word and has employed it many times.

What follows is a serious analysis of horseshit. I am not trying to be crude. I want to educate and initiate you into the language of baseball, a language I came to as an adult.

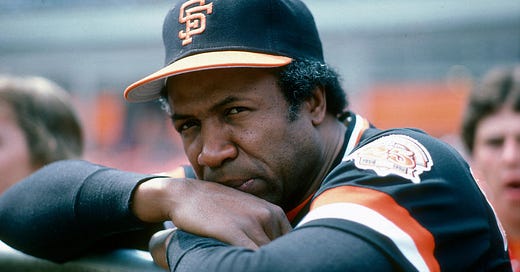

I will talk about Frank Robinson who was a connoisseur of horseshit, but he is representative of every baseball player. Robinson was a Hall of Fame outfielder and manager of the San Francisco Giants where I met him. If Frank didn’t like a column I wrote, it was a horseshit column. Sometimes he called me a horseshit writer, which I took in stride. At least we were communicating. If he objected to a reporter’s question he’d shoot back, “That’s a horseshit question.” This I heard hundreds of times. If one of his outfielders threw to the wrong base, it was “a horseshit play.” If the postgame meal served on large trays in the clubhouse didn’t appeal to him, it was “a horseshit meal.”

Horseshit was Frank’s go-to, all-purpose pejorative, as it is in every clubhouse in the big leagues. One day Frank didn’t like the positioning of his fielders during batting practice. Too many crammed near the middle of the field. So, he yelled, “Spread out the horseshit,” as he waved his arm indicating where he wanted his players to move. Horseshit becoming a noun. A versatile word.

My enduring fondness for the word is strange considering I didn’t grow up with it. I grew up with bullshit. And that in itself is strange because in Brooklyn there are more horses that bulls. I checked the internet and Brooklyn has horse stables and riding academies galore. I couldn’t find a single reference to bulls. So, horseshit should have been our preferred curse word in the 1950s, but bullshit was. Which means I was a late convert to horseshit.

What does horseshit mean?

According to Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary Eleventh Edition horseshit is a vulgar term meaning “nonsense, bunk.” Let me stop here and admit I should have gone to the Oxford English Dictionary for a fuller explanation. Now you see the level of my scholarship. I’m a horseshit scholar and that explains why I fled academia and ended up in the sports pages.

Anyway, I disagree with Merriam-Webster’s definition which I consider a horseshit definition. Bunk and nonsense are closer to bullshit than horseshit. Bullshit is phony stuff, and a bullshitter is a phony and a liar.

Horseshit is an all-purpose term of condemnation, especially the way it’s used in baseball. It denotes displeasure, unhappiness and scorn. Something that is no good. It is not nonsense or bunk.

I don’t blame the folks at Merriam-Webster’s for getting it wrong. How many of those word geeks spent any time in a big-league clubhouse trying to scrounge a quote off a pissed-off pitcher after a loss? Merriam-Webster’s knowledge of horseshit is strictly second-hand, probably from what their editors have read or been told. Did Barry Bonds ever rush into the offices at Merriam-Webster and scream, “Your definition of cosmology is horseshit.”

If this were an academic essay, the kind I learned to write at Stanford, I’d pause right here and summarize before moving on.

Summary:

Horseshit is a simple, direct, aggressive term conveying displeasure, annoyance, anger. It means something or someone is subpar, doesn’t meet the mark, stinks. Anyone who says horseshit is seriously pissed off. When Frank Robinson said I was a horseshit columnist he was not accusing me of nonsense or bunk. He couldn’t have cared less about nonsense or bunk. He was saying I suck, plain and simple, probably because I had criticized him in print. For me, he was speaking a new language. When I failed a test, my father never said, “That’s a horseshit result, Lowell.” He said, “You need to do better, dear, to get into a good college.”

What is bullshit and how does it differ from horseshit?

Merriam-Webster does better with bullshit than horseshit. As a noun the dictionary defines bullshit as “nonsense: foolish, insolent talk.” As a verb Merriam-Webster comes up with: 1. “to talk foolishly, boastfully or idly. 2. to engage in a discursive discussion: to talk nonsense with the intention of deceiving or misleading.”

For further elucidation on the word bullshit, please read Harry G. Frankfurt’s delightful little book On Bullshit (Princeton University Press) which should be required reading at every American university and in Congress and the White House. I am not kidding. This book really exists.

I will make one more point, although I’m not sure what it amounts to. Bullshitter is a word but there is no word horseshitter.

So, what’s the point of all this? When I was introduced to the word horseshit, a whole new world opened up to me, the Christian World populated by big-league baseball players from America’s Heartland – the South and Midwest and Texas, guys who chewed tobacco and spit on the dugout floor or during interviews collected the spit in empty Coke bottles to avoid spitting on the clubhouse carpeting, and me watching in horror and wanting to vomit.

Johnnie LeMaster, a wonderful guy, is a Southern Baptist who lives in Paintsville Kentucky and used to play shortstop for the Giants. He once asked my religion. “Guess,” I said. He said, “Protestant.” I said, “No.” He said, “Then you must be Catholic.” I smiled and said, “I am Jewish.” He looked confused. He wasn’t aware of Jews, couldn’t imagine what a Jew looked like.

But baseball talk united Johnnie and me and all the ballplayers. When they called my writing or my question or my jacket horseshit, we were speaking the same language, the lingua franca of baseball. I had come from grandparents who grew up in the shtetl and spoke only Yiddish, from parents who spoke Yiddish at home and English in the New World, and I had learned Hebrew at age eight, but through the linguistic idiosyncrasies of baseball – I’d call them linguistic glories – I learned to talk American. To be American.

Excerpted from my memoir in progress, Brooklyn Jew.